Heart Rate Variability (HRV) & Mind Training

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a valuable indicator of mental and physical health. It can quantify your energy levels and even predict when your heart will stop beating.[1]

Given the mind-body connection, this could theoretically measure your mental fitness progress. So is HRV a useful biofeedback tool for meditation? Here’s the science behind HRV and how you can impact it through mind training.

What is Heart Rate Variability?

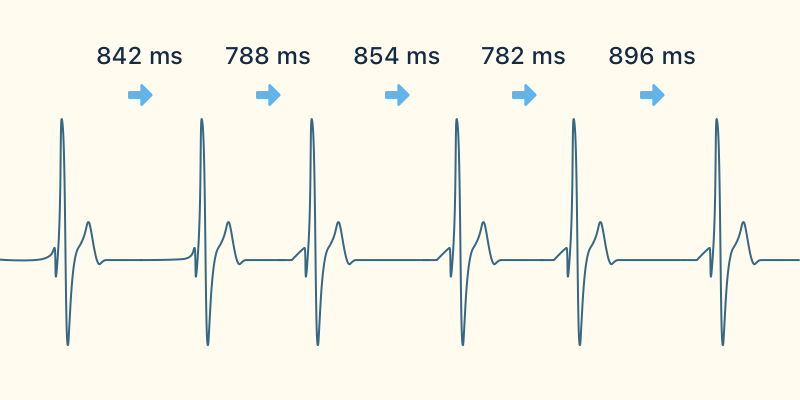

HRV measures the different intervals between your heartbeats over time. So while heart rate records your beats per minute (bpm), HRV tracks the variance in your bpm.

For example, let’s say your heart rate is 60 bpm. That doesn’t mean it actually beats once every second. You might see 0.9 seconds between beat on the inhale and 1.1 seconds per beat on the exhale.

There’s variance between heartbeats, which is your HRV. One common way of calculating HRV is by taking the root mean square of the successive differences (RMSSD) between heartbeats. The average HRV score for athletes is about 59.

When your breath is in synchrony with your heart, you’ll generally see a shorter interval between heartbeats on the inhale and an elongated interval on the exhale.

This variance is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). It occurs because your inhale activates the sympathetic nervous (fight-or-flight) system and your exhale activates the parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) nervous system, telling your heart to speed up and slow down respectively.

HRV has different frequency bands (ranges), separated into high-frequency power (HF) at 0.15 - 0.40Hz and low-frequency power (LF) at 0.04 - 0.15Hz. The LF/HF ratio may estimate the ratio of sympathetic/parasympathetic nervous system activity, although this is controversial.

In general, you want to see a higher HRV, which means that your body is more capable of adjusting to and recovering from stressors. It’s a sign that your nervous system is in good health and responsive to environmental demands.

Low HRV, on the other hand, typically means that either the sympathetic or parasympathetic branch (usually the former) is dominating. This could indicate a lack of sleep, dehydration, or illness. HRV also tends to decline with age.

HRV During Meditation

Since most meditation techniques activate the calming parasympathetic nervous system, we’d expect to see an increase in HRV during those methods.

Several studies have measured the effects of meditation on HRV. Here are five examples and the conclusions they reached:

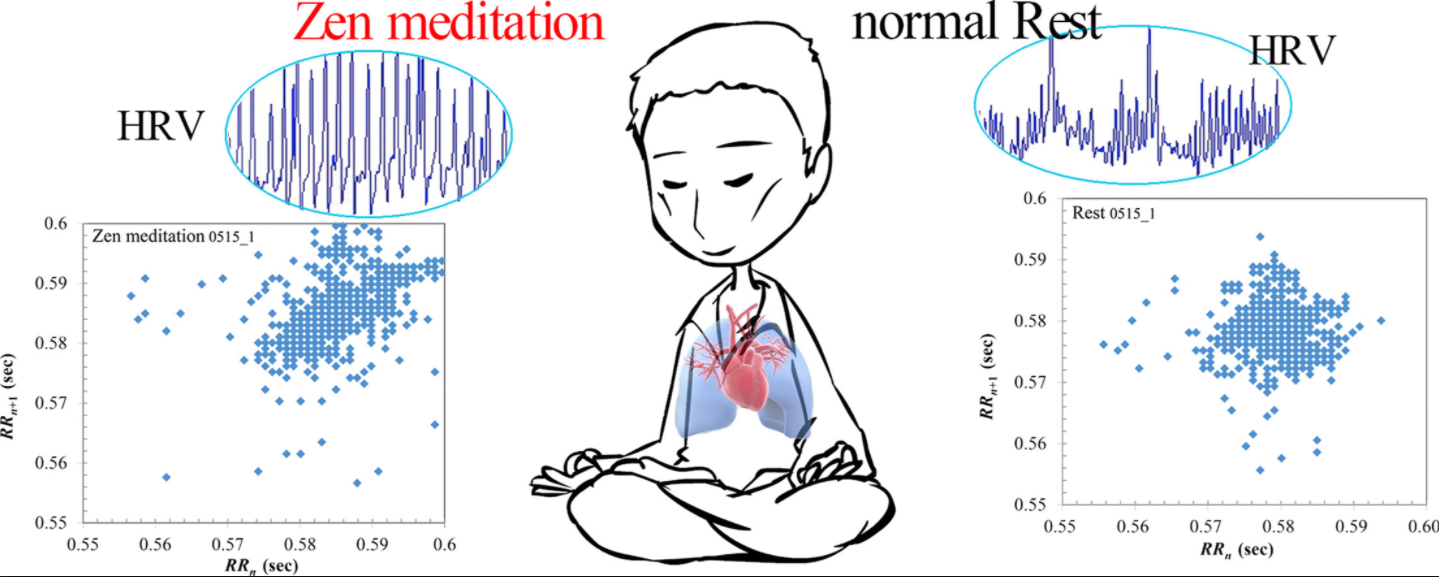

Inward-attention meditation increases parasympathetic activity: a study based on heart rate variability, Wu et al., 2008. “The results revealed both common and different effects on HRV between inward-attention meditation and normal rest. The major difference of effects between two groups were the decrease of LF/HF ratio and LF norm as well as the increase of HF norm, which suggested the benefit of sympathovagal balance toward parasympathetic activity.“ In short, meditation improved short-term HRV in ways that normal rest did not.

Changes in heart rate variability during concentration meditation, Phongsuphap et al., 2007. “Our study revealed that heart rate variability during concentration meditation was changed from the normal state in a systematic way.”

Increased heart rate variability during nondirective meditation, Nesvold et al., 2011. “HRV increased in the low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF) bands during meditation, compared with rest.”

Individual trait anxiety levels characterizing the properties of zen meditation, Murata et al., 2004. “During meditation, in terms of mean values in all subjects, an increase in slow alpha interhemispheric EEG coherence in the frontal region, an increase in high-frequency (HF) power (as a parasympathetic index of HRV), and a decrease in the ratio of low-frequency to HF power (as a sympathetic index of HRV) were observed.” [Note: Crucially, this study parsed out meditation and paced breathing vs. just paced breathing and found that the meditation component had an effect on HRV over and above simple breathing interventions.]

Cardiorespiratory and autonomic-nervous-system functioning of drug abusers treated by Zen meditation, Lo et al., 2018. “Among 18 voluntary drug addicts during the 10-minute Zen meditation session, about two-third subjects have significant improvement in autonomic nervous system function characterized by heart rate variability (SDNN, RMSSD and pNN50).”

Lo et al. (2018) showed an increase in HRV during Zen meditation for the majority of subjects.

However, other studies have found more complicated links between meditative states and HRV:

Zazen and cardiac variability, Lehrer et al., 1999. “Heart rate variability significantly increased within this low-frequency range but decreased in the high-frequency range (-.14-0.4 Hz), reflecting a shift of respiratory sinus arrhythmia from high-frequency to slower waves.” [Interesting excerpt from this study: “One Rinzai master breathed approximately once per minute and showed an increase in very-low-frequency waves (<0.05 Hz).”]

This contrary finding may result from the fact that different styles impact the nervous system in unique ways. The above study conducted by Lehrer et al. focused on slow breathing meditation, a different task from the inner focus meditation in the first study by Wu et al. We would expect the PNS to become dominant with slow breathing, which would likely lower HRV.

Other studies have looked at changes in resting baseline HRV over time, as opposed to during meditation training:

Central and autonomic nervous system interaction is altered by short-term meditation, Tang et al., 2009. “Differences in heart rate variability (HRV) and EEG power suggested greater involvement of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in the IBMT group during and after training.”

Mindfulness meditation, well-being, and heart rate variability, Krygier et al., 2013. “There were no significant main effects of time (pre- vs. post-Vipassana) on HRV.” [Note: Measurements were taken an average of four days after the program ended.]

Finally, one study compared the impact that different types of meditation had on HRV. It looked at how training over time impacted HRV:

Is meditation always relaxing?, Lumma, et al., 2015. “The increase in HR and decrease in HF-HRV over training was higher for loving-kindness meditation and observing-thoughts meditation compared to breathing meditation.”

So there are varying results and we need some further research before drawing conclusions. However, given the limited data set, we can make a couple of best guesses about HRV and meditation training. First, meditation likely impacts the autonomic nervous system in the short term, as indicated by significant changes in HRV. This implies that HRV is a psychophysiological marker of progress in meditation.

Here’s a personal measurement plotting heart rate over time during a tranquil breathing meditation. Notice how the measurements form a relatively regular sine wave. Learn More: A Complete Guide to Breathing in Meditation

Second, the long-term impact of meditation on HRV is unclear. Since many general health-related factors influence HRV, this is a difficult area to study.

And third, not all types of meditation impact HRV in the same way. Meditation is a broad term, like “exercise,” which covers many different techniques that work the mind-body system in different ways. Hopefully, future research will clarify which meditation styles correlate with changes in HRV.

Meditation HRV Biofeedback Training

Currently, some apps provide first-generation meditation biofeedback training, including Zendo for Apple Watch, Oura Ring, and HeartMath.

While the FitMind team considered licensing a technology for our app that would allow meditators to measure HRV during meditation, we ultimately decided against it. We just don’t know enough yet to make accurate claims about HRV and meditation. Furthermore, a previous guest on The FitMind Podcast, Judson Brewer, told us that he studied meditative states and HRV in 300+ fMRI runs and found no correlation.

Instead, FitMind uses a brief self-review each day, asking members to rate themselves in a few key areas: presence & focus, emotional control, social connection, and mental energy. We believe that, for now, self-observation is still the best way to measure your progress in meditation.

P.S. — If you’re serious about learning these techniques and deepening your meditation practice, check out the FitMind meditation app.

Sources:

[1] La Rovere, Maria Teresa, et al. "Short-term heart rate variability strongly predicts sudden cardiac death in chronic heart failure patients." circulation 107.4 (2003): 565-570.